Active Adaptation For Neck Pain

Active adaptation for neck pain is a comprehensive therapy that focuses on aspects of the patient’s environment or lifestyle that have the potential support or interfere with progress. The three general categories addressed are significant others, exercise, and relapse prevention.

A. The significant other is typically the spouse or life partner of the patient; however, children, parents, roommates, or other individuals with whom the patient lives and interacts daily may be as important to include in treatment as the spouse. It may begin with an initial evaluation, which provides for a glimpse into the attitudes and responses of others and how they influence the patient. Persons who are frequently in contact with the patient may inadvertently reinforce pain behavior by providing pain contingent rewards, such as attention, assistance, or sympathy. Their expectations may unknowingly discourage efforts at reactivation. They may be urging the patient to continue to search for a cure and undermine efforts to use the self regulatory techniques being taught.

Active adaptation for neck pain focuses on educating significant others about the pain, the objectives of treatment, and the ways in which they can support rather than inhibit progress contributes to successful treatment outcome. Recognition and acknowledgment that those close to the patient have also suffered consequences, such as changes in assignment of household responsibilities, reduced or eliminated social activities, and financial problems, promotes mutual efforts by patient and family at healing the resentments that can accumulate. A family session may be scheduled in a clinical setting for this purpose.

B. Exercise, is addressed from a motivational perspective that has the goals of decreasing resistance, encouraging effort and establishing a regimen that can be independently maintained. The specific exercise regimen is determined and supervised by the treating pain specialist. Pain patients are often reluctant or fearful about activation, and they self sabotage by either not completing homework assigned by the physical therapist or by overdoing, thereby confirming their belief that exercise will make their pain worse.

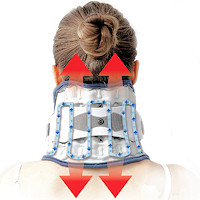

In many cases inactivity or immobilization has been directly rewarded by an initial reduction in pain, however, over time, this leads to muscle atrophy or wasting, so that periodic efforts at activity or use of the injured part results in more pain and leads to a greater chance of immobilization. This is particularly true of neck pain, where decreased range of motion resulting from pain is often treated with a cervical collar or brace on which the patient becomes dependent.

In active adaptation for neck pain therapy, patients should be aware that some amount of increased pain results from increased exercise, however, there is a difference between hurt and harm, using both the relaxation skills and the thought changing (cognitive-reframing) techniques can help the patients’ persistence in the effort needed for improvement.

Patients can be shown how exercise can decrease depression, reduce insomnia, promote production of endorphins, assist in management of stress, control weight, and, by increasing muscle tone and circulation, improve their health in general.

Neck Traction Devices Neck Traction Devices |

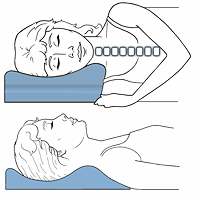

Cervical Pillows Cervical Pillows |

Head Supports Head Supports |

C. Relapse prevention is where patients are taught the importance of thoughts to both affect and behavior and are instructed to expect periodic and temporary increases in pain, and are to think of these episodes as flare-ups rather than setbacks. Through experience they can understand that response to a flare-up has less averse impact, and that they have been equipped with tools to lessen rather than inflame the flare-up.

In addition to teaching an adaptive response set to pain fluctuations, relapse prevention is primarily aimed at prevention; “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Working in concert with a pain-specialist occupational therapist, patients are instructed in time management and pacing. They are shown, for example, how attempting to outrace pain on good days in service of task completion contributes to occurrence and prolongation of a flare-up.

Active adaptation for neck pain sessions make use of daily schedules, where they are helped to implement and maintain appropriate regimens that include exercise and relaxation. Patients are also given instruction in sleep hygiene, because insomnia is such a common problem for pain patients. They are helped to establish regular hours for sleep, eliminating naps during the day, and are directed not to eat, read, or watch television in bed.

Relaxation exercises designed specifically for sleep enhancement may be taught, and tapes with the exercises can be given for nightly use. Stress management training is another important topic in relapse prevention. Patients learn how to modify and use the relaxation and cognitive techniques for stress reduction, and the role of exercise and nutrition. Communication skills training and assertiveness training are incorporated into this aspect of the treatment plan as well. All aspects of relapse prevention emphasize ongoing patient awareness and responsibility for application and maintenance of all they have learned, and thus responsibility for management of their pain.

A 2014 review in Psychology Research and Behavior Management, there are distinct philosophies and effects of psychological intervention focusing on the ways that pain affects psychological functioning.

The next part is Coping with Neck Pain Conclusion